Diffondiamo:

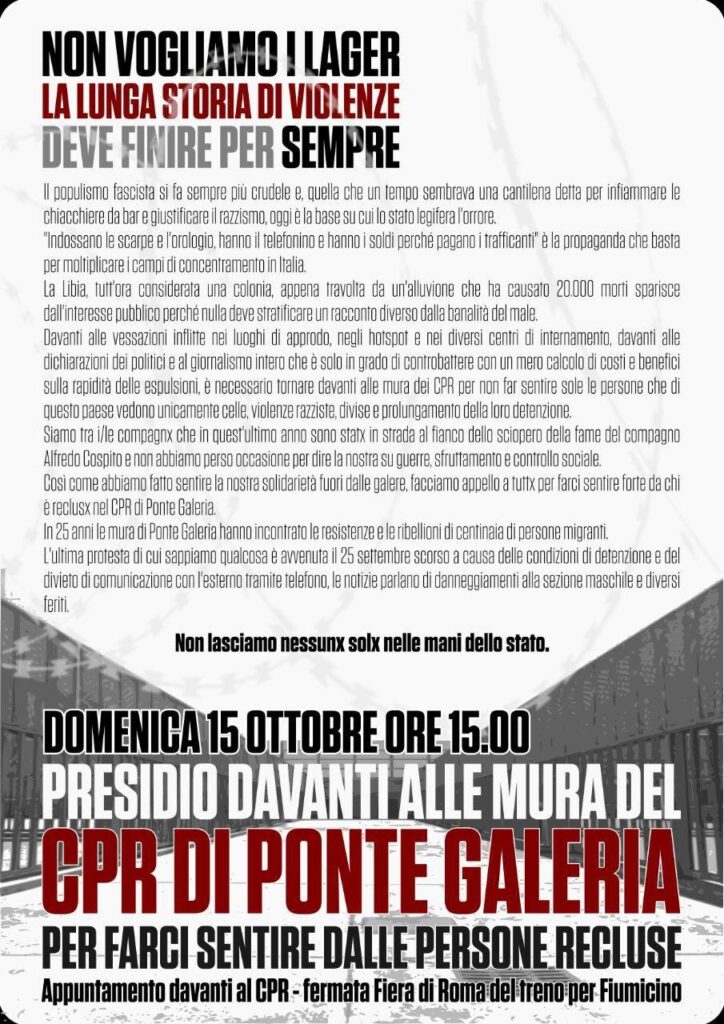

Non partiremo dalle botte, dal fatto che ci hanno strappato via un compagno, dal fatto che nei CPR torturano e che dai CPR deportano.

Non partiremo da questo perché non sarebbe il discorso di Jamal.

Pertanto non è e non sarà il nostro.

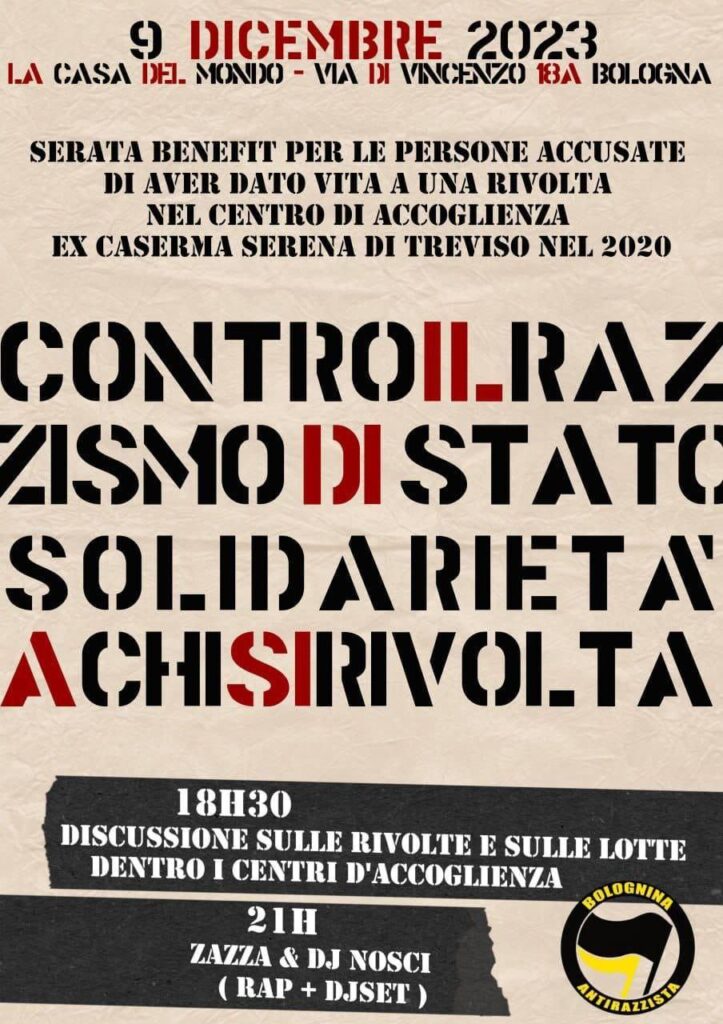

LE RIVOLTE

Un anno fa il CPR di corso Brunelleschi bruciava. Bruciava e chiudeva grazie al fuoco dei ribelli. Quelle colonne di fumo che si stagliavano al cielo emanavano la forza di una rivolta, dando coraggio a chi, fuori, coglieva quel momento per immaginare una solidarietà che nelle sue possibilità riuscisse ad essere palpabile ed efficace. Che potesse superare quel tempo e quel luogo e rimanere solida nelle sue prospettive di lotta contro la detenzione amministrativa, la macchine delle espulsioni e il razzismo sistemico e sistematico.

LEGAMI E ALLEANZE

Jamal è un pezzo di questa storia, è il segno profondo che il rapporto tra un dentro e un fuori è stato auspicabile, possibile, reale. Che organizzarsi insieme è un orizzonte non solo desiderabile ma realizzabile.

In questo anno abbiamo provato a tessere i nessi di senso che legano la guerra esterna – che ha raggiunto il suo apice con il genocidio palestinese – insieme alla costruzione del nemico interno – inquadrato per lo più tra il sottoproletariato razzializzato e chi lotta. Abbiamo ribadito, sempre più convint*, che creare qui alleanze di lotta con chi subisce l’oppressione di classe e lungo la linea del colore è il nostro punto, il nostro orizzonte, la nostra strada.

TENTARE IL POSSIBILE

Jamal è un nostro compagno, un nostro amico. Ha fatto questa strada con noi e non potevamo che tentare il possibile: inceppare il suo trasferimento in un CPR, dove per 18 mesi può essere sottoposto a detenzione e violenza, può essere torturato, per poi, un giorno, arrivare alla deportazione.

Mentre sotto i nostri occhi si muovevano gli ingranaggi del razzismo di Stato, non potevamo permetterci di rimanere inermi.

La macchina delle deportazioni e della detenzione amministrativa si compone di tanti piccoli pezzi: dalle perizie medico legali delle ASL, alle imprese che costruiscono e/o gestiscono i centri di detenzione; dai rastrellamenti degli sbirri durante le retate, ai voli charter che realizzano le deportazioni.

Ognuno di questi tasselli è più vulnerabile di quanto non sembri nel suo insieme il moloch delle detenzione amministrativa.

La sorpresa e la difficoltà degli sbirri nel dover gestire lo slancio di solidarietà di fronte alla questura ne sono la conferma.

IL COPIONE DEI MEDIA

La copertura mediatica dell’accaduto ha seguito un copione decisamente rodato: una comunicazione dell’ufficio stampa della questura viene inoltrata e ripubblicata da agenzie di stampa e giornali senza la minima rielaborazione.

E così gli aggressori diventano aggrediti e i professionisti della violenza (coloro cioè che della violenza istituzionale fanno la propria professione) passano per vittime.

Spariscono i pugni in testa, le manganellate scomposte, le minacce, gli insulti. Nella narrazione univoca e standardizzata delle veline poliziesche, sparisce la radice stessa della violenza, quella dei meccanismi di potere e dei dispositivi di governance delle classi sfruttate, quotidianamente emarginate, discriminate, incarcerate, espulse. Unica vera notizia (nel senso di fatto degno di nota) in questo caso è stata la “necessità” da parte della polizia di dispiegare appieno questa violenza per portare uno “straniero” nel CPR di Milano, un posto – tra gli altri destinati alla detenzione – disumanizzante al punto da creare scandalo per la gestione delle persone recluse.

Se in questi giorni la brutalità della polizia è balzata agli onori delle cronache per alcuni casi di violenze perpetrate durante momenti di protesta, la storia di ieri può aggiungere allora un prezioso tassello alla comprensione dei meccanismi che regolano e reggono le iniquità sociali: i poliziotti non picchiano solo ai cortei, non colpiscono solo gli avversari di questo o quel governo. I poliziotti pestano tutti i giorni, per garantire a suon di botte che la società dello sfruttamento rimanga tale.

Sappiamo che su Jamal è caduta più potente la brutalità della repressione perché ha scelto di lottare, ha scelto di organizzarsi. Il colpo e i colpi di oggi però non sono niente in confronto alla rabbia che abbiamo nel cuore e all’amore che arde questa lotta e ci lega alle compagne e compagni che troviamo lungo la strada.

MANTENIAMO VIVA LA SOLIDARIETÁ!

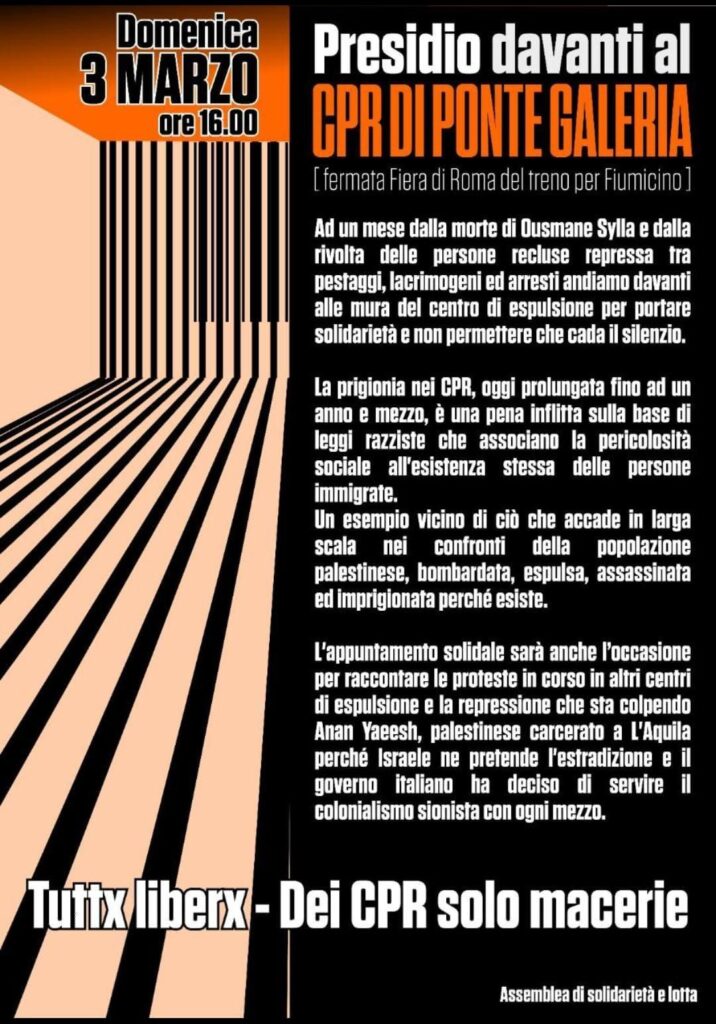

PRESIDIO SOTTO LE MURA DEL CPR DI VIA CORELLI DI MILANO

10 MARZO 2024 ORE 15

Il fuoco dei CPR brilla ancora e il coraggio delle lotte e delle rivolte stenta a placarsi.