Pubblichiamo la traduzione in inglese di un articolo suddiviso in due parti condiviso di recente “FRONTIERE, MILITARI, SBIRRI E CPR : UNA NUOVA ACCELERATA DEL RAZZISMO DI STATO IN ITALIA”. Ringraziamo The Blackwave Collective che ha curato la traduzione affinchè l’articolo raggiunga quante più persone possibili, oltre barrirere linguistiche e frontiere.

Di seguito la prima parte (qui in italiano).

We receive and disseminate the first part of a text written by several hands by comrades fighting against Detention Center for Repatriation and borders between Italy and France. In the text, an attempt is made to make a synthesis of the European trends of recent months and the recent decrees passed by the government.

At this link, the second part.

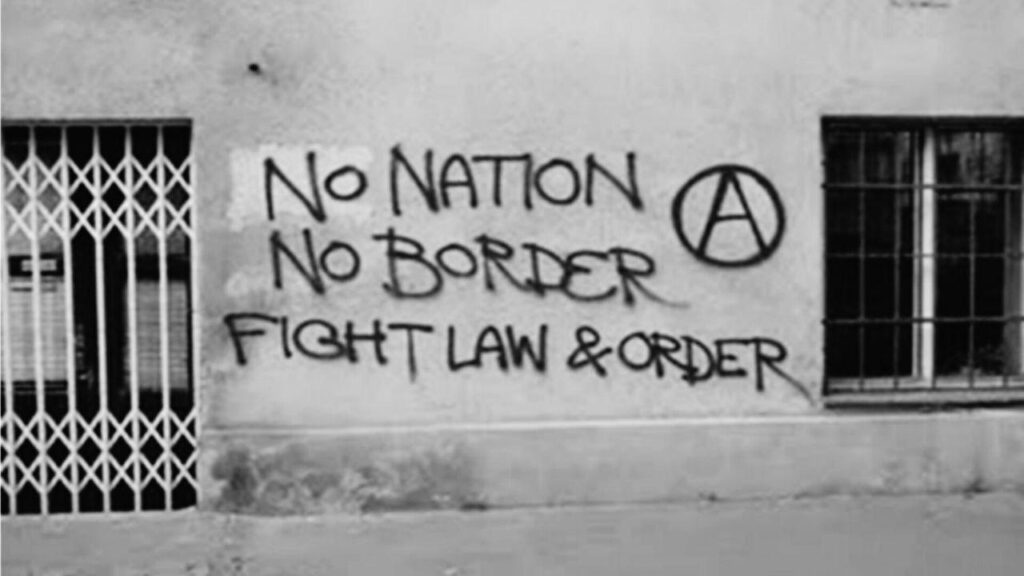

Talks about repeated “migration crises” are a great classic of domestic and European politicians and newspapers. These narratives serve to justify the repression and exploitation of migrant people on European soil. In practical terms, exploitation and racist repression are sustained at the national level by a legislative production made up of decree-laws and at the supranational level by the relentless establishment of treaties and agreements. The ever-increasing presence of militarized borders, cops and jails for undocumented people are the practical implications of these policies.

The “Lampedusa crisis” of recent months, which has seen thousands of people stranded in a semi-prison situation on the island, seems to have accelerated some trends in Italian migration and border management. This text wants to try to dwell on some recent changes (especially from the legislative point of view) to give some small elements of analysis to those who fight against state racism, its jails and its borders. In particular, we will try to trace the latest developments concerning the role of Frontex in Europe, the trends in some European countries on the issue of administrative detention and deportations, and the latest decrees in Italy.

THE ROLE OF FRONTEX IN EUROPEAN BORDER GOVERNANCE

Before we look at what the Italian government has come up with in recent months, let us start with some general trends dictated by internal EU guidelines and policies. The management of the internal borders of European countries is linked to the surveillance and repression activity carried out along the border with non-European countries.

This activity manifests itself concretely in two ways. On the one hand, it results in the militarization of borders through the strengthening of operations conducted by European agencies in charge of defending national borders, primarily Frontex. On the other, there is an increasingly systematic process of outsourcing European borders through the investment of large sums of money intended to finance gradually sharper surveillance technologies, with the creation of detention centres and camps in non-European and transit countries.

Without wishing to go too far back in time, let us try to draw some lines on the European Union’s investment in this area over the past year, particularly since the outbreak of war in Ukraine. The conflict has produced increased scrutiny of Europe’s eastern borders, which crossed by a significant flow of people fleeing and an even greater flow of armaments sent

to the front lines (1). Ukraine historically plays a role in regulating Europe’s eastern border, consquently, the instability in this area has resulted in a strengthened of Frontex in its territories.

The beginning of 2022 marked by the deployment of Joint Operation Terra, an operation that sees dozens of troops deployed across twelve European states, particularly in the eastern European regions (Estonia, Romania, Slovakia). In addition, the agency has initiated several joint operations with states bordering those regions desigend to train local armed forces and border police. The stated aim is to increase the capacity of these countries to protect their borders by combating “illegal” immigration and “migrant smuggling” and consequently defending Europe’s borders. Frontex’s intervention in 2023 concentrated in Ukraine and Moldova due to heavy pressure from people fleeing the Russian-Ukrainian conflict and, in the Balkan area, particularly Macedonia and Romania. (2)

Border management in the Western Mediterranean works quite differently and follows the structural emergency model. While preferential humanitarian corridors opened in Ukraine, which saw the transit of large numbers of (white) migrants, 2367 people died at sea in the Mediterranean in 2002. In the first seven months of 2023, about two thousand people died, including several hundred in two shipwrecks between February and June. On the night of February 25-26, a boat slammed into a shoal off Cutro, Calabria, and capsized in the waves, leading to the deaths of 94 people. In the wake of the massacre, controversy will abound over the role of Frontex and the Italian coast guard in predicting the shipwreck (3). On June 16, 2023, a fishing boat sank off Pylos, Greece, killing 750 people, one of the worst shipwrecks in recent years, yet another massacre caused by Europe’s deadly border management policies. Again, the responsibility of the Coast Guard is mentioned (4). Meanwhile, monitoring activity by Frontex in the Mediterranean underscores the strong presence of irregular immigration in this region, which justifies the intense repressive action conducted by the European agency in the waters between Sicily and North Africa.

Against this backdrop, we arrive at the last months of summer 2023, when, within a short period, numerous boats cross the Mediterranean, leading to an increase in landings on Lampedusa. These partly determined by the tug-of-war between Saied, the Tunisian president, and Brussels over the release of funding under the memoranda with Tunisia.

In the face of the manu militari management called for by Prime Minister Meloni and supported by Von Der Leyen’s proclamations declaring a hard fist against the “traffickers responsible for the thousands of landings,” Frontex says it will increase its support for the Italian police force, doubling the number of hours patrolling the Mediterranean and allocating contingents in Reggio Calabria and Messina to facilitate and speed up the procedures for identifying and expelling irregular migrants. In addition, Frontex has made it clear that it is ready to organize identification missions in non-European countries to facilitate return procedures based on the needs of Italian authorities (5). Recall that the agency is present in Italy through Operation Themis, which consists of 283 units, five vessels, seven aircraft, 18 mobile of fices and four migration control vehicles. In this scenario, in the logic of outsourcing, Frontex would like to expand its influence in Africa. The agency is in talks with the governments of Senegal and Mauritania for direct action on the ground through the deployment of its contingent (6).

We can see that, as far as the management of Europe’s external borders is concerned, EU countries tend to delegate more and more to non-European countries the blockade of flows through Frontex-led military operations and by financially financing local armed forces. At the same time, the discourse of the “migration emergency” makes it possible to justify increasingly repressive measures that serves on the skin of those who try to cross borders. This also brings consequences for laws enacted at the European level.

EUROPEAN TRENDS: MORE PRISONS AND MORE DEPORTATIONS

Whether what is moving at the continent’s external borders and the latest round of decrees in Italy, must be read in parallel with ongoing trends in the European space at large. Two dimensions seem particularly important: the European pact on migration and asylum and national plans to restructure detention and deportation systems.

The European Pact on Migration and Asylum is a European Union project that has not yet been adopted but expected to pass in 2024, before the European elections. Although it has presented as major innovation (repressive, of course), this pact does not seem to have invented much, but it could accelerate mechanisms already in place. The pact provides, among other things :

- to more tightly bind non-European countries’ obtaining visas to travel to Europe in exchange for consular laissez-passers to be able to deport even more undocumented people to those same countries. France has been doing this for quite some time: either you agree to “repatriate” tuX illegals, or I will cut off your visas.

- to systematize the screening of asylum applications at the external border, in continuity with the hotspot approach and the latest Italian decrees;

- reforming the Schengen treaty: the possibility of re-establishing border controls between European countries (as has been happening for years between France and Italy) and launching joint police operations against “irregular movements”;

- to further strengthen European databases in which to record the identities of foreigners arriving on the continent “illegally” and-or asylum seekers (e.g., by extending the time frame in which to keep the fingerprints of people intercepted at the border so that it becomes even more complex to apply for asylum in a country other than the one in which one arrives);

- of suspending everything “in case of crisis” or “instrumentalization”: accelerated asylum procedures a bit for all, imprisonment in Detention Center for Repatriations if there is a “risk of flight,” etc.In reality, these are not new measures, and it is hard to know at what point the pact will transform the current situation or merely legalize at the European level what is already happening in various countries. Instead, the point that seems most innovative is the one that concerns the mechanisms for redistributing asylum seekers (the famous Dublin Regulation), which has always been a significant element of tension between the governments of the countries on Europe’s southern and eastern borders and those in the centre and north. All the theatre that the Italian government has been doing in recent

weeks is also related to this: which state should “take care” of the new arrivals, locking them up in centres, judging whether they can stay in the territory, and possibly sending them back-and where did they come from?

The European pact provides three options for EU countries :

- either they agree to “relocate” (as if they were parcels) asylum seekers intercepted at external borders;

- or they must contribute financially to expulsions by other European states;

- or else they participate (economically and logistically) in European external border controls.All this stuff is called “European solidarity”: if you don’t want to participate in the control and selection of poor immigrants, hunt for money to expel them.Beyond the legal framework they are working on at the European level, several EU countries are already implementing similar mechanisms concerning the administrative detention and deportation system. Several European states are fine-tuning the deportation machine, such as Spain, where two years ago they built what is probably the biggest Detention Center for Repatriation in Europe in Algeciras, 500 places (7), or such as Germany, where the Detention Center for Repatriation at Berlin’s Brandenburg airport is going from 24 to 108 places (8), and where they are talking about lengthening administrative detention from 10 to 28 days (9).

Specifically we do not know if there is any indication from the EU to this effect-the project that the Meloni government (and others before it) is pursuing to systematize the imprisonment of undocumented persons by increasing the length of administrative detention and building a Detention Center for Repatriation in each region is just what has been happening in France for some time. In 2019, there will be an increase from 45 to 90 days of detention. By 2025, according to the Macron government’s plans, the additional places in administrative detention places will be more than thousand, plus or minus 75,000 more prisoners per year. A new CRA (the French Detention Center for Repatriations) inaugurated in Lyon, several centres opened in Mayotte (an island off the Indian Ocean considered to be a French department) during the neo-colonial operation known as Wambushu, and new constructions planned in Orléans, Nantes, Bordeaux, Dunkirk, and Paris (next to Charles de Gaulle airport, where there is already a CRA) (10). It’s not over: in early October, French Interior Minister Darmanin announced six more new CRAs to double the number of places in administrative detention. There is also talk in France of lengthening administrative detention to 18 months for “foreign offenders.”

NOTE

(1) Recall that a few months before the outbreak of the conflict, another “migration crisis” erupted at the Polish-Belarus border. Pressure from hundreds of people from the Middle East and Africa transiting Belarus led to massive border crossings between December 2022 and March 2023, resulting in a militarization of the Polish border and the construction of a barbed wire wall between the two states.

(2) All operations in which Frontex is engaged are publicly available in the news section of their website.

(3) https://www.repubblica.it/cronaca/2023/09/06/news/cutro_naufragio_dati_frontex_migranti-413503943/